Strong supply and favorable interest rates mean 2025 could be a more stable year for the machinery...

Celebrating the History of the Manure Spreader

The manure spreader may be considered by some to be the lowliest of all farm implements. Yet, considering that in the past it was one of the most frequently used implements on many farms. Weighing the huge impact it exerted on reducing the back-breaking labor to spread manure across fields, enriching them, and boosting yields, the manure spreader deserves a prime position in the pantheon of farm machinery advances.

The history of the manure spreader is somewhat shrouded in the myths of implement lore. One of the earliest patents filed on a manure spreader dates back to May 10, 1859. Numerous additional patents were filed in the 1860s.

Research backed by references in C.H. Wendel’s book, American Farm Implements & Antiques, provides strong evidence that one of the first successful manure spreaders was built in 1875 by Joseph Sargent Kemp of Magog, Quebec.

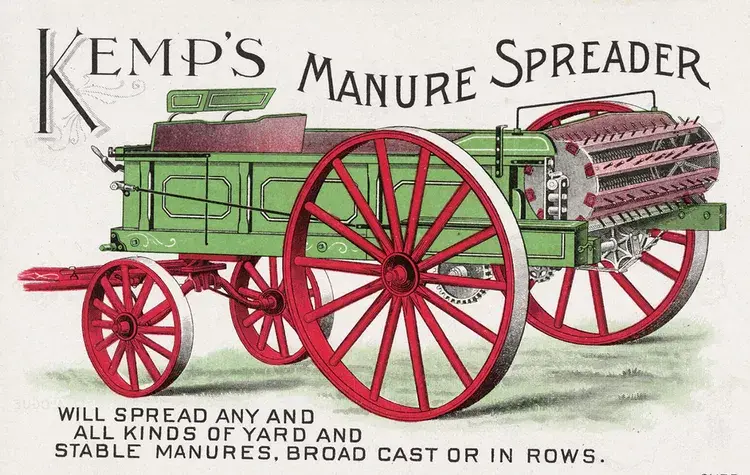

Kemp’s Success spreader

Kemp would later move to Newark Valley, New York, where he started a manufacturing plant to build his design. In the ensuing years, he would file numerous patents on his spreader designs, and his firm would take on a partner (There are references to a Kemp & Burpee Mfg., Co. in Syracuse, New York, in 1895.) and expand to Waterloo, Iowa, in 1903. That same year, Kemp sold some – but not all — of his spreader patents to International Harvester.

Promotions of the day confirm that the Kemp design, dubbed the Success spreader, employed a type of moving floor (likely an endless apron with wooden slats) that fed manure into a single tine-adorned horizontal cylinder at the rear of the wagon. Yet, little is known of Kemp’s floor design.

During the late 1800s, dozens of companies would introduce spreaders on the market employing Kemp’s basic design with slight variations. Eventually, spreaders came to employ two tine-encrusted cylinders to further shred and fling manure.

Enter Oppenheim and his New Idea spreader

Spreaders at this time did have a major drawback. They were capable of shredding manure directly behind the spreader but did little to distribute it in a wide pattern to the sides of the wagon. Often, heavily straw-laden manure would clump in a band at the back the spreader.

Aware that farmers often had to take harrows out in the field to further spread manure, Joseph Oppenheim, a schoolmaster in Maria Stein, Ohio, came upon an improvement while watching schoolboys hit a ball with paddle bats. The direction of the hit ball, he saw, was greatly affected by the angle of the paddle.

The New Idea spreader made extensive use of roller bearings to ease the draft on horses. Its paddle spreader design flung manure out the rear of the spreader both to the back and the sides, which improved distribution.

Oppenheim envisioned a series of paddles mounted at an angle on an axle rotating horizontally that would fling materials further afield. He would go on to patent his concept, which he dubbed the New Idea, and began building a spreader marketed under that name in 1899.

Sales of New Idea spreaders grew rapidly, so much so that the company opened a second factory in 1907. Less than a decade later, the New Idea Spreader Company enjoyed sales of $1.2 million.

The huge demand for spreaders was not lost on major manufacturers. As mentioned before, International Harvester Company (IHC) had bought some of Kemp’s patents, employing them to build and sell the Kemp 20th Century spreader first introduced in 1905.

International quickly expanded its spreader line to include design variations sold under the Clover Leaf, Steel King, and International names, as well. The IHC wagons employed an endless apron with wooden slats (comprising the live floor) that moved the manure into spreader mechanisms. The Corn King spreaders even offered a reversible apron. With this device, the apron was wound over a drum for unloading.

A major advance at this time, which was seen in the IHC spreaders, was the ability to adjust the speed of the live floor. The ability to adjust unloading to match the manure load enhanced spreading quality and also prevented plugging at the rear beaters.

In time, the wooden slats in live floors would be replaced with iron slats connected to drive chains. These slats would slide over a solid wooden floor and work to simplify spreader operation while enhancing its durability.

Deere’s entry into spreaders

Records indicate that in 1902, John Deere was selling the Kemp and Burpee’s Success spreader. Deere would go on to buy that firm in 1910 and begin making the Success spreader in its East Moline, Illinois, plant. Both Kemp and his business partner, Burpee, would join Deere with that acquisition.

In the meantime, Deere engineer extraordinaire Theo Brown patented a spreader whose beater was directly driven over the wagon’s rear axle. The major advantage of this design, combined with front wheels that were mounted close together under an extended gooseneck frame, was that it created a spreader that featured a much lower wagon.

Low-slung spreader

As a result of these improvements, Deere’s models B and C stood just 36 inches from the ground to the top of their boxes. This advance made loading the spreader easier, since farmers didn’t have to pitch manure over wagon sides that were almost as tall as they were. These low-slung spreaders could also be readily driven under short barn doors.

The unloading and beater drive mechanisms of spreaders of this time were beefed up and simplified, eliminating complicated clutches and drive chains.

In the 1930s, the predominantly wooden boxes of manure spreaders were replaced with steel sides, which were more durable. Also, at this time, came the advent of PTO-driven spreaders that greatly enhanced the ability to adjust the implement to unload more evenly while reducing plugging.

EDITOR’S TAKE:

Growing up on a dairy and hog operation, I find this historical perspective interesting, especially since I can relate to how the machines actually operated. Yes, the design improvements were important back in the day. Fast forward to today and there is no comparison at all to the machines used in the past. Sure, you can still purchase a manure spreader today, but most manure is injected or knifed into the ground. Modern soil testing and GPS help guide where nutrients are needed. Government regulations also help dictate where and what can be top-dress applied or has to be spread in some other manner. Today’s “manure management systems” are complex and expensive. You can help keep those operating expenses lower by promoting AgPack®, now with up to $40,000 available through exclusive discounts and rebates when farmers/ranchers purchase or lease their qualified truck or SUV from you, a CAD member!